Trade, the Lifeblood of the Ancient Civilizations

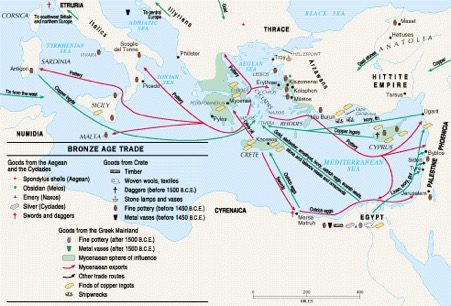

Mycenaean products, especially pottery, were exported to southern Italy, Sicily and the Aeolian islands, while other products travelled into Sardinia, as well as southern Spain. In Bavaria, Germany, an amber object inscribed with Linear B symbols has been unearthed. Mycenaean bronze double axes and other objects dating from the 13th century BC have been found in Ireland, along with items found in Wessex and Cornwall in England.

Anthropologists have also found traces of opium in Mycenaean ceramic vases, which is no surprise as the drug trade has been traced back as early as 1650 BC, with opium poppies being traded across the eastern Mediterranean.

Reconstruction of a Mycenaean ship (CC BY 3.0)

Like Crete, the Mycenaean lands had no natural supply of precious metals. Their economy depended entirely on agriculture and trade. They traded what they had in order to get what they needed. Mycenaeans were well known for their perfume, wine, wool and pottery. One of their chief exports was olive oil, a multi-purpose product in high demand. Penelope, the wife of an olive farmer, would have helped to produce the highest possible quality oil for the export market. Whether they produced grades of oil for the various uses such as perfume, is assumed but not confirmed.

International trade was not only conducted by palatial emissaries, however, but also by independent merchants. The reasons for such an unexpected and widespread development of exchange lie in the strengthening of the central power and in the increased demand of metals that the Mycenaean leaders needed to procure from foreign markets.

In the period, copper came primarily from Cyprus. Some tin was imported from Turkey and Cornwall, but the majority came from Afghanistan. Tin was to the bronze age civilizations what oil is to modern man - a crucial commodity. By combining the two metals, they made bronze, which is harder than copper and easier to cast. It is also harder than pure iron and more resistant to corrosion. The discovery of bronze was a major advancement in metallurgy during the Bronze Age and allowed for the production of more durable weapons, armor, and luxury objects.

Both the Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations established wide-ranging networks throughout the Mediterranean. Evidence of trading contacts from as far away as Kush (south of Egypt) and Afghanistan has been found in Aegean Bronze Age archaeological sites. (Ablongman)

The Mari letters, which dated to 1800 BC and were found in the king’s burnt library in what is now Syria, talk about tin being traded with various nations, and the vast trade distances. If one trade route was cut, it created havoc for other nations and at a time when there were skirmishes across the Middle East, delivery was never guaranteed.

During the First Palatial period, Crete obtained its metal resources, like tin and copper, primarily from the Near East and Anatolia. However, by the beginning of the Second Palatial Period, the Near East and Anatolia were rife with warfare. Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and Syria were affected by the Hittite Old Kingdom and the growth of the Hurrians, while in Egypt, there were wars with the Hyksos. These periodic bouts of war not only disrupted trade routes but would also have increased the demand for the metal. This may have initially pushed the Cretan palaces to look for alternative sources, like Mycenae, whose trading network included the regions of the Balkans, the Alps, and central Italy.

The Mycenaeans also imported raw materials such as gold, glass, hippopotamus ivory, and lapis lazuli. They traded for finished goods - spears, shoes (from Crete) and jewelry. At the same time, the ordinary sailors, traders, and people who came into contact with foreign merchants were trading ideas, concepts, stories, beliefs and myths. Working for a merchant, Phyllidos who lived on the small island of Salamis in the Aegean Sea, would have had frequent contact with citizens of these great civilizations.

Mycenaean pottery has been found in Egypt, the Levant, Sicily and Italy and a great number of imported luxury items have been found in Mycenaean graves along with a great number of imported vases which confirms the commercial exchange. Furthermore, one of the graves in Grave Circle B at Mycenae (17th – 16th century BC) contained the earliest finds of amber within Greece – a total of 122 pieces. This suggests that the occupants of these graves were able to control and maintain large amounts of amber supplies from the Baltics. An Adriatic connection is likely given that Mycenae was well-placed and located along the quickest routes to the west and north of the Mediterranean, through the Bay of Napfalion and the Gulf of Corinth. Mycenae could well have acted as a gateway community in this trade network.

Embassies and trade delegations ensured continued relations with foreign nations and they influenced a wide-ranging audience, even down into Africa. Egyptian plaques of Amenhotep III have been found nowhere else in the world apart from Egypt and Mycenae, which must indicate a special relationship. The name of Queen Tiye, wife of Amenhotep, has also been found at palaces in Mycenaean towns. Names of Mycenaean villages were discovered on the base of Egyptian statues found at of Colossi of Memnon dating to 1360 BC. The town names are thought to be some sort of itinerary for a diplomatic trade trip.

The discovery of the Gelidonya and Uluburun shipwrecks has given historians and archaeologists an even more valuable glimpse into the trade routes of Bronze Age nations. It is thought that the ship found near the coast of Gelidonya, off the coast of Turkey, sank in the 13th century BC and was either Phoenician or belonged to a travelling metalsmith of Cypriot or Syrian origin. This was the oldest known shipwreck until the discovery of the Uluburun shipwreck in the early 1980s. Thanks to these two ships, we now know that the ancients were knowledgeable seafarers who built a ‘global economy.’

Ancient Mediterranean Civilizations: A Captivating Guide to Carthage, the Minoans, Phoenicians, Mycenaeans, and Etruscans by Captivating History 2020

Uluburun Shipwreck exhibit. It took 10 years and 22,000 dives to salvage the wreck, which lay under 50 meters of water. (Public Domain)

The artifacts aboard the Gelidonya and Uluburun wrecks convinced George Bass, the father of underwater archaeology, that ancient Mediterranean maritime trade had not been dominated by Mycenaean Greeks, a view that had been adopted based on finds of Mycenaean artifacts at a number of land sites. Instead, Bass believed that Near Eastern seafarers controlled those ancient trades and seas.

The older Uluburun shipwreck was discovered off the coast of Asia Minor and could have been heading home to Mycenaean ports with a full cargo. It has also been proposed that it hailed from Canaan or Cyprus.

Among the finds on the Gelidonya shipwreck were Mycenaean pottery, scrape copper, copper and tin ingots, and merchant weights.

The Uluburun ship carried a diverse cargo of raw and manufactured luxury items and commodities from at least 11 far-spread ancient cultures, ranging from the Baltic to Equatorial Africa, the Mediterranean world, and the Near East. The cargo matches many of the royal gifts listed in the Amarna letters found at El-Amarna, Egypt. Amongst the items were raw copper totaling ten tons and approximately one ton of tin, jars filled with glass beads, olives and pistachio resin to make an ancient type of turpentine, approximately 175 glass ingots of cobalt blue, turquoise, and lavender, logs of blackwood from Africa, tortoise shells, ostrich eggshells, Cypriot pottery and oil lamps, agate, carnelian, quartz, gold, amber and a gold scarab inscribed with the name of Nefertiti, various weapons, and edibles such as nuts, fruits and spices. This incredible hoard was worth an absolute fortune and its loss must have been devastating to the owner.